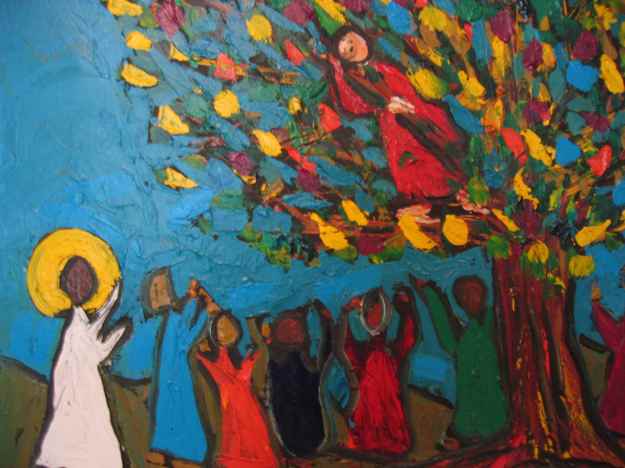

Image: Zaccaeus, by Joel Whitehead

An old sermon (from 2001)…

Luke 19:1-10

Jesus’ encounter with Zacchaeus is a story that recapitulates all the great themes of Luke’s gospel: the anticipatory mercy of God, the joy in heaven when the lost are found, the moral precariousness of the self-made and the self-righteous, the necessity of deeds to authenticate righteousness – especially the divestiture of concentrated wealth and the just treatment of the oppressed.

It is also a charming story, filled with unexpected details that make it easy to imagine. We learn that Zacchaeus was short, that he ran fast to beat out the crowd, that he climbed a tree, and that it was a sycamore. We learn that, inexplicably, Jesus knew his name, and that on the spur of the moment he invited himself to eat and even to stay overnight at Zacchaeus’ house. When we hear that Zacchaeus responded without the slightest hesitation, we imagine him flattered, flustered, happy, hopping up and down like a child.

But he was no child. He was a grown man, but exactly what sort of man is hard to say. His name means “clean,” or “pure,” but his profession was anything but. He was a chief tax collector with jurisdiction over a prosperous region, raising revenue from Jews for the foreign occupier, a collaborator consorting with Gentiles. To ordinary people tax collectors were disloyal opportunistic extortionists, Roman lackeys. Religious professionals held them in contempt as the most impious of sinners. It would not surprise me to learn that even their Roman employers despised them.

And yet…

And yet, there he is, a tax collector running after the rabbi, eager for Jesus, going out on a limb heedless of possible scorn or injury, unconditionally responsive when Jesus calls him down, illustrating another of Luke’s great themes—that only outsiders and outcasts recognize the kingdom when they see it.

Now, there are outcasts and there are outcasts. Most of Luke’s outsiders, even the morally shaky ones, elicit our sympathy. Widows, possessed people, lepers, women about to be stoned—when they fling themselves at Jesus’ feet, beg for mercy, confess their sins, or clutch his hem in search of healing and a restored life, we feel the injustice, the pity and the pain of their ostracism.

But a tax collector? That’s a different animal. If Zacchaeus is as nasty a piece of work as his contemporaries assume, it seems like just-desserts that he should be shunned in polite company and blotted out of the Book of Life. We could be wary of Jesus’ apparent approval of him in the same way that we are often upset by the characters in his parables who get a lot more than they deserve: Why the favor shown to the prodigal brat and not to the older son? Why a full day’s wage paid to the man who worked only an hour? Why eat with Zaccaheus? Zacchaeus is the kind of outcast we would feel OK about leaving out there beyond the pale. He brought it on himself.

But is he really all that bad? Consider this: when the crowd begins grumbling about what a disgrace it is that the rabbi should lodge with a sinner, Jesus, who usually delivers withering zingers in response to such judgments, says nothing. Zacchaeus is the one who speaks. He delivers a vivid self-defense. And what he says precisely has long been a translators’ debate. It all depends on whether you render his verbs, which are in the present tense, as “future-present” or “customary-present.”

The more traditional approach has been to use the future-present. In this rendering, Zacchaeus has a converting encounter with Jesus, and because of it, from now on he will behave more justly. Meeting Jesus changes him, on the spot, from a bad man to a good man, concerned with fairness and the well-being of the poor.

But in many other gospel scenes in which conversions occur, there are always dialogues of repentance and forgiveness, requests for restoration from the supplicant, and the commending of faith from the savior. None of these typical exchanges happen here. So other scholars prefer to render Zacaaheus’ speech in the customary-present. When they do, what Zacchaeus claims is that all along he has been more generous, more scrupulous, and more self-aware than he’s been given credit for. His self-defense is a simple disclosure of fact: he has habitually given half what he owns to the poor—that’s 40% above the tithe—and whenever he discovers that he has been involved in a fraud, he makes a four-fold restitution—twice what the law required.

He makes this disclosure not as a boast to God, like the prayer of the Pharisee in the temple we read about last Sunday, but as a plea for vindication, a plea that Jesus answers by recognizing him, a rich man, as a true son of Abraham, ready for the kingdom with all his household. Here, then, is another characteristic Lukan theme: although it is indeed harder for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God than for a camel to pass through a needle’s eye, for God, all things are possible. Zacchaeus is living proof of God’s power.

Zacchaeus’ disclosure of his generous and just practice was also surely meant as an act of hospitality: after all, Jesus is his guest, and the grumblers are ruining dinner. If Zacchaeus can correct their judgment of his own morality, maybe they’ll stop heckling Jesus about his choice of host. But I doubt he was able to accomplish that, especially if there were Pharisees in the crowd, who, fairly or not (and mostly unfairly), the evangelists depict as men devoid of irony who wouldn’t know a nuance or a compromise if one rose up and bit them, and whose notions of goodness and religious purity were not susceptible to the kind of truly human complexity we may have in Zacchaeus.

And it is human complexity in all its infuriating nuance that is on display here. Zacchaeus is a man carrying out one of those morally-dubious jobs, like designing missile guidance systems. Yet we cannot simply say that he is corrupt: the very thing he gets right in his life is the same thing God has put forward since the dawn of creation as the touchstone of authentic humanity and right worship: care for the poor and justice for the oppressed.

If “customary-present” is the better way to understand Zacchaeus’ response to the critics, it makes the story more familiar to us, and maybe even more credible. Zacchaeus is not converted on the spot—this rarely happens in human experience, and it doesn’t happen here. No, it turns out that he is neither villain nor hero. Neither consistently evil nor an exemplar of consistent virtue. But in a few important areas of his life, he is capable of acting like a man of God, a true son of Abraham, and the effects of his conduct on the world around him are humanly profound.

He is, then, like most of us, a compromised man in a compromised world, leading an ethically-ambiguous life in an ethically-bewildering human landscape. His name notwithstanding, he is unable to be pure in a world that is not pure either.

Like Oscar Schindler, a man not to be trusted with your money or your wife who saved thousands of Jews from destruction.

Like Mother Teresa, a woman supported by donations from organizations opposed to population control in India who gave dignity to the dying and hope to the sick and a new way of service to countless young people.

Like me, when I went to give a talk to some church leaders at the home of the congregation’s head deacon, a fifteen room house on eight acres in Sudbury, more house than any Christian should need or want, I remember thinking judgmentally as I pulled up to the front door, only to be greeted by seven adopted special needs children living happily inside.

This is Zaccaheus, complex and compromised in a complex and compromised world. Jesus loves him, accepts him fully just as he is, and glowingly commends him to Pharisees, to bystanders, and to us.

As I ponder his story, I find myself thinking about the anxiety, apprehension, anger, and frustration running rampant in our roiled-up nation and our war-torn world. We have great need of unambiguous prophets, strong and fearless, who will go way out on a limb and scout a new humanity, a different way, who will speak uncompromisingly the language of peace. But I am also thinking about the hideous consequences of true believing, whether it comes from “them” or from “us,” the frightening fundamentalisms of the right and the left, about the bloody dangers of replacing our first allegiance to human beings with ideology of any kind.

I am thinking about how difficult it is to be pure without being proud. I am thinking about the need we have for truth, and the fact that truth always comes to us unpackaged, in fragments, never unalloyed. I am thinking about the wisdom, the humility it takes to know that, and still to dare.

I am thinking about our communities of faith and witness, imperfect and loved by God; full of people with strong minds and wills, fierce convictions and bright visions; deep and faithful people who are also, at the same time, weak and needy, sinful (I begin with me), plagued by mixed motives and impure hearts, who live in a complex and ambiguous world with which we compromise daily despite our rhetoric of ethical excellence and moral purity, despite the high standards we often hold each other to and the judgments we make about each other when we fall short.

I am thinking about whether we should even try to come before God in any other way except in our frank human nature, full of our ambiguity; and whether, perversely, we should be relieved and even glad that it’s hard and even dangerous to be pure.

And I am thinking gratefully of you, First Church, for if any grumblers should question whether we are an appropriate house for Christ to lodge in, we also can, like Zaccaheus, say in our own defense that by the grace of God, in the midst of our compromises and sins, we do care for the poor and we do work for justice; that at least we know that that is the thing we should be trying to get right, no matter what else we may struggle with, fail at, or fudge.

I am thinking how grateful I am, and I hope you are too, for this odd privilege of being accepted by a God who knows our dilemma, who shared our flesh, experienced our internal contradictions, was done to death by our compromises, and who loved us first, still loves us now, and will keep loving us to the end.