Genesis 1:9-13; Matthew 13: 1-9; 18-23

I am a city person, terminally urban. When we bought our last house, a handsome historic Greek Revival, it was in Somerville, the most densely-settled 4 square miles in Massachusetts. Unlike our former dwelling, however, this house had a small yard, and the previous owner had made the most of it. She’d created a beautiful blossoming border all around the big old house.

After we signed the papers and moved in, it took me a couple of months to understand that along with the house we’d also bought the garden. It took me another month to realize that somebody would have to take care of it! That turned out to be me.

Now, I’d never gardened before, but I came eventually to love weeding and watering, fertilizing, planting and planning. I appreciated even the yucky tasks — setting beer out for the slugs and picking off the crimson bugs that threatened the lilies.

Acquiring a love for something changes your outlook. You pay attention differently. Before I had the garden, I listened to weather reports to decide what to wear or to find out if the Sox would play. After I got started in the garden, what I wanted to know most was whether there’d be a long, soaking rain overnight, or whether I’d have to get up and lug the hose around. How long would the muggies last? Would there be a thunderstorm with damaging hail that could break the blue spikes at the back of the border?

Another thing the garden taught me was that you cannot accomplish everything all at once. I learned that it was bad for my back and bad for the garden to do too much, to spend hours on end fussing at it. But by tending only one part, doing only one chore carefully each day, the border of blossom around my house thrived, and I did too.

At first light and at last, I would sometimes go outside just to look at it, and people used to stop and look at it with me. And when they complimented me, I felt almost humiliated, struck in my soul by the disproportion between my efforts and the garden’s beauty. I’d think to myself, “Nothing I did made this happen.”

Thus I discovered anew the paradox everyone who deals in creativity and beauty knows well: if I hadn’t worked hard at my garden, it would have been a tangled mess. You know the old joke about the minister who stopped on his morning walk to admire a neighbor’s garden. The neighbor was weeding and watering, and the minister couldn’t resist a theological reflection: “Isn’t it wonderful,” he gushed, “what human beings and God can do together!” The sweaty man looked up and said, “Sure is, Reverend. You shoulda seen this garden when God was doing it alone!” Without me — no garden. But I had nothing at all to do with the beauty and pleasure it became for me and for others who saw it. The garden was in fact an extravagant gift.

Jesus says: A man went out to plant, scattering seed everywhere. Some never sprouted — the birds got to it first, or it landed on soil too rocky for roots. Some seed that did germinate got choked off by weeds, and some couldn’t get enough sun. But some fell on good earth: it got the right light and enough rain, and yielded thirty, sixty and a hundred-fold. Jesus explains: the seed is the word of God. Not everyone who hears it will take it in. But if we do, what can happen to us is beyond dreaming.

I used to hear this story as a summons to examine yourself, feel guilty and get busy. Am I the rocky soil? Do I choke off the voice of God in my life like thorns? Maybe I’d better pile on more compost, weed more diligently, shoo away cats, squish bugs and drown slugs with greater and grimmer determination. But too much of this sort of thing turns the parable into a spiritual work ethic — not Jesus’ point, I think.

As practically everyone knows by now, if you’ve ever sat through a sermon on this story, in the Palestine of Jesus farming could be a real hit or miss operation. You went out, tossed the seed indiscriminately, and hoped for the best. The best was about ten-fold. So when Jesus says that his fictional farmer might get a hundred percent yield, real farmers probably laughed in his face — it was beyond anyone’s experience.

Jesus was making an agricultural promise he couldn’t keep. But he was making a spiritual promise he had absolute confidence in: God wants to produce that kind of yield in our lives, in our human garden. This is a parable about a God who can and will make much more out of our efforts to be beautiful and fruitful than is proportionate. I know this now that I know a little about gardening.

God asks us only to come to terms with the fact that we bought the garden along with the house, and to cultivate what has already been planted in us. Just to tend a little to it, routinely — ruminating on the scriptures, worshiping with a community of faith, asking for what we need in daily prayer, giving thanks to God for all we have and for who we are, trying to bring the wisdom of Christ to our lives in small things and large, never getting out of daily touching distance of real human suffering, resolutely resisting the little evils that populate our day, putting ourselves in the way of beauty, meeting the lovely neighbor, welcoming the stranger and loving the enemy, letting ourselves fully enjoy the pleasure of the simplest things, and disciplining ourselves to believe that God is passionate about us and desires our good (for of all the tasks of the garden, this one is perversely the hardest of all).

After a while we’ll begin to feel a certain devotion to our tasks. We’ll begin to feel a need to be doing small things daily. And that in turn will become a blessed routine without which we will feel odd, at sea, a little off kilter. And gradually, this simple daily discipline will become a deep passion. What was a chore will become a gift.

We will begin paying attention differently too, hearing differently and caring differently. Our interests and priorities will begin to shift. We may judge with more compassion and less narrow-mindedness. We may be less self-interested, more concerned for the good of people who are lacking and vulnerable. We may become less obsessed with our image or abilities, more settled and self-accepting, more open to others and less self-protective; more able to forgive and be forgiven, more able to relinquish our securities and our firmly-held but rarely thought-through opinions; more painfully aware of the pain of the world; more creative in making a difference even in the smallest of ways; more able to enjoy and more gratefully able to give and receive pleasure.

And after a few seasons of such patient daily tending, we will begin to experience that same paradox that people who deal in creativity and beauty know: the harvest we will have become is not of our own making. Rather, it will strike us as a great and extraordinary gift, full of mercy and mystery.

And when others start noticing our more centered lives; when people are attracted to God because of us; when someone inquires about our gardening secrets and growing tips, we will respond not in false modesty, but in all truth: we did not make ourselves loving and just; we did not by our own wisdom and skill help someone in our family change and live; it was not our effort that produced a reconciliation or a compromise in our circle of friends; it was not just our organizing skill that prompted the company to act more fairly or the politicians to work more diligently for the good of all. We will live gratefully in the great wonderment of the hundred-fold yield. All along it was God, we will say, all along it was the Spirit in us, just as Jesus promised.

And when we use the word “grace,” we will know whereof we speak: we will have become intimately persuaded that life is not about achievement, acquisition and productivity; not about earning God’s, our own, other people’s or some free-form cosmic approval; not a protracted struggle to get the love we never got and wish we had (and that would never be enough for us anyway), but about love already given and available in infinite supply, about gifts bestowed and received, mercy showered down and soaked up, and blessing all around. We may plant and weed and water, but God alone makes things mature, including us, including justice, including happiness, including desire.

God wants to give us this ridiculous, unbelievable yield. Maybe it’s hard to accept that we could be the object of this kind of generosity, hard to credit that God could be so besotted with us. But it’s the message of Christ, and we can at the very least try to live as if we know it to be true, in a daily discipline of refusing the internal voices that tell us it can’t be. If we get even that far — even if all we have is desire — God’s creative commitment to us will make us joyful, grateful cultivators of the gardens God gave us to tend: our souls and bodies, the family we live in, the town we are citizens of, the nation and world for which we bear responsibility, and the church wherein we learn about and celebrate the beauty of God’s work. And we will bear fruit, thirty, sixty, one hundred-fold.

You can trust God to produce this beauty, to produce it with or without you, whether you’re lugging a hose or taking a nap in the shade. You can trust that God will bless with extravagant yields your desire as well as your deeds, your deeds that flow from desire, and your sighs too deep for words.

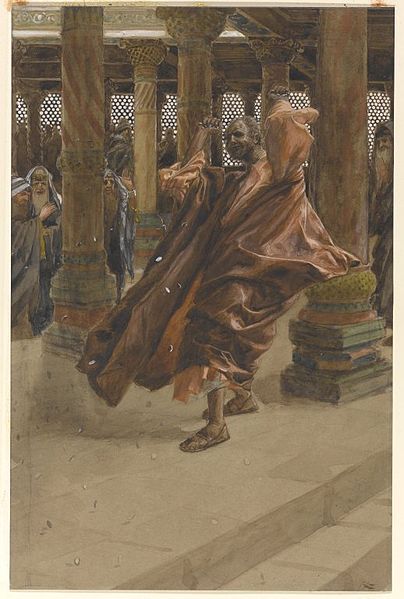

Christ the gardener greeting Mary: Lavinia Fontana, “Noli Me Tangere,” 1581