The tree of Life, allegory with birds perched on branches. Mosaic pavement; 4th century CE

The first gift God gave humans was to make us from clay, to give us kinship with dirt. God named the first earthling adam, meaning ‘human,’ from the root word, adama, meaning ‘soil.’ To be human is to be grounded, in the earth. And when we remember that we’re dust, when we know our place, we become wise. And that’s a great gift.

The second gift God gave humans was breath, kinship with God, a sharing in God’s own life. The adam is related to God by breath, and every breath the human draws is full of God’s own desires. The earthling resembles God in this way: he’s drawn to beauty and full of appetites.

Which is one reason God gives adam another gift, The Garden, “beautiful to look at and good for food.” In the Garden, he could satisfy his desires, especially his desire for God. For God lived in the Garden too, strolling in the cool of the evening among rocks and plants and streams, with kitties, kangaroos, earthlings, earthworms, bunnies and bears.

And that was the way it was, once in a Garden—shared life, companions and kin, creatures all, made-in-the-shade of the Tree of Life that grew in a Garden near Eden, in the East of God’s new and wonderful world.

Now, it wasn’t all play and no work for the human. The world outside the Garden was perfect, but unfinished. Help was wanted: an on-site tiller of soil, someone who would care for the earth. God made the world with room in it for involvement and participation, for evolution and improvement. That’s why God made the earthling, the first gardener.

You’ve probably heard that God commanded Adam and Eve to ‘fill the earth and subdue it.’ To multiply and have dominion. And God does say that, in one story. The Bible has two creation stories, and in the second, God doesn’t say ‘fill and subdue,’ but till and care. The first story leads to possession and mastery. But the second story leads to belonging and participation. In this story, the humans have work to do, but it’s joyful work, because when they care for the earth, earth cares for them, too.

Then the story takes a sad turn. A smooth talking serpent appears and plants seeds of mistrust in the human heart. And that mistrust becomes a wedge. It splits things:

Humans had never felt shame in being naked; now they do. Their relationship with their own bodies is broken.

Once they’d walked with God; now they’re afraid of God and try to hide. Their relationship to God is broken.

Once they called each other ‘my own flesh and blood’; now they turn on each other in accusation and blame. Their relationship to other humans is broken.

God closes the Garden and sends the humans into the world outside. There they discover that their relationship to nature is damaged too. Participation in the world now brings suffering as well as joy. The story says that’s a punishment, but it’s not really. It’s just that we’re so deeply connected to the world that when things aren’t right with us, they’re wrong in nature too. And nature won’t be right again until we are.

But even with all its hardships, the world was still wondrous. Yet it never fully satisfied us like the Garden did. We planted garden after garden ourselves, hoping to sense God’s footfalls in the grass, to see flowers that don’t fade, to hear God speak to the heart. But nothing we made was like what we lost.

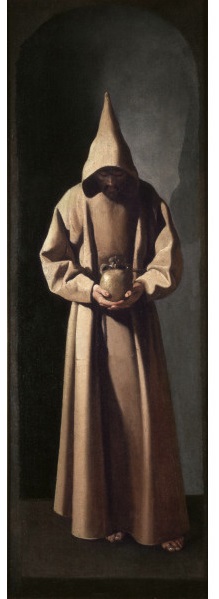

The story goes in many directions from here. For Christians, it goes to Jesus, God’s Child. The story says he came to find and stay with us who’d become so lost and lonely. He left his own Eden with God and took an earthy body, just like ours.

But by then, we were so practiced in ignoring our kinship with creatures and God that when he came to us in human flesh, breathing the divine breath, we did to him what we were doing to each other.

We treated him like a foreigner, even though he stirred a deep memory when he told stories of gardens and seeds, trees and birds, lilies, and harvests gathered into barns.

We said we didn’t know him, even though he ate, drank, sang, and danced with the happy abandon of one who knew what life was like in the Garden.

We regarded him as a stranger, even though we heard the accent of Eden in the way he talked and felt its cool breezes in the way he lived.

In a cruel twist, when we seized him, it was in a garden. And when killed him, we buried him in one too.

The ancient creeds say that as soon as he died, he descended to a gloomy place where for eons long-dead ancestors were waiting for the Messiah. Jesus “harrowed” them. That’s an old word for raking. Like a harvester, he raked them up and gathered them into his new life. Later, back at the garden tomb on Easter morning, Mary Magdalene saw him, but she thought he was a gardener. She wasn’t really wrong.

Genesis is the Bible’s first book. It recounts the first creation. Revelation is the Bible’s last book. It promises a new creation when time ends. The new earth, it says, will be like a jeweled city with walls and towers, but in its center God will plant a Tree of Life, just as God did once in a Garden.

The Tree will yield a different fruit each month, and its leaves will be medicinal for the nations—for all people, no matter who. A Tree of diversity and healing, a Garden undefiled. It’s hard to imagine. We hide guns in our gardens. We bulldoze thousand-year olives. We delude ourselves, thinking we can demean, ignore, unhouse, and kill each other, and exploit water, earth, air, and animals, and suffer no lasting harm.

But now, as we witness the effects of our self-delusion, the truth scripture teaches is stark. In disappearing ice caps and disappearing bees, in bad water and very sick children we see plainly that there’s no separation between human beings and nature, between this nation and that nation, between this continent and that island, between our own generation and those to follow. We’re in this together. For better, and for worse.

Some people say it’s too late for the earth, too late for us. But although earth has been entrusted to our care, it’s still God’s earth, not ours. We can either believe that or we can despair. It’s still God’s creation. We can either trust God or despair.

I think we won’t despair. I think we will read and study and pray the Garden story, over and over. I think we’ll speak to each other about Eden and the earth, about creatures and God and divine breath, about Adam the gardener, and Jesus, the new Adam, the harvester of life. I think we won’t despair because we have this great green story and in it, a mission and a calling.

I think we won’t despair. I think we’ll ponder how to invest our money and how to reduce our footprint and how to organize and how to protest and how to vote. I think we’ll do all those things and more.

And it won’t seem like much against the odds. But each small thing we do will be a kind of remembering. Each small step a re-connection of broken kinship, an act of love. Small thing by small thing, we will become ourselves a Garden, an oasis, a taste of Eden, at play and at rest as God intended for us and every creature under heaven. Small thing by small thing, by endless grace and persevering response to grace, God’s glorious will for the earth and for all creation will shine and shine again.

“Teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.” — Psalm 90:12

“Teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.” — Psalm 90:12