TEXT: Matthew 13:13-17

Not every story about Jesus made it into the gospels. And not all the gospels tell the same stories. The angel Gabriel appears to Mary only in the gospel of Luke. Jesus turns water into wine only in John. And only Mark ends his account of the resurrection on a note of fear. Different communities prized different stories. So when a story shows up in all four gospels, you know it represents an early Christian memory that everybody thought was too important to leave on the cutting room floor. Jesus’ baptism is one of those stories.

We always read it at the start of the Epiphany season between Christmas and Lent. It’s a season of insight and revelation, when hidden things are made plain. All the gospel passages assigned to Epiphany’s Sundays shed a little light on the mystery of who Jesus is. As we watch him speak and act in these stories, our picture of him clarifies, and we catch glimpses in him of who God is and what God is up to in the world.

And sure enough, in Matthew’s version of the baptism story, we get a big revelation about who Jesus is. It comes right after Jesus wades out of the Jordan. The heavens open, the Spirit alights, and a voice declares, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved, in whom I delight.’

But we also learn a little more about who God is and what God wills. There’s no thunderclap, bright light, descending bird, or James Earl Jones voice accompanying this revelation, however. To see it, we have to go back to the flustered conversation John has with Jesus in the opening lines. Did you notice it?

Jesus presents himself for baptism, but John doesn’t seem pleased. He doesn’t say, “Good morning! No matter who you are or where you are on life’s journey, you are welcome here.” He says, “I know who you are. Please go away.” He tries to prevent Jesus from being baptized. “Me?” he says. “You want me to baptize you? You should be baptizing me!”

Why does John try to keep Jesus out of the Jordan?

The clue is in the kind of baptism John was offering. John was baptizing ‘for repentance.’ He believed the messiah had come. That’s why he’s preaching a message of urgent change. And, we read, crowds of people were coming to him, ready to repent of their sins, change their lives, and receive the appointed one.

They symbolized their willingness to change by immersing themselves in the river. They washed away their sins, they sloughed off their old lives, they left all that sorrow, hurt, and regret in the Jordan, and went away to live clean in the new age that was already dawning.

And now, here is that new age in person—Jesus of Nazareth, the messiah, the sinless one, God’s chosen person. But if that’s who he is, what’s he doing here lined up with sinners? Why is he asking for a washing? Isn’t he already clean? Besides (and here’s a second clue to the revelation), isn’t it humiliating for someone ‘high up’ like Jesus to be baptized by someone ‘down low’ like John?

John is the opening act, not the main event. The understudy, not the lead. The bridesmaid, not the bride. So how can an inferior baptize a superior? That’s not the way the world is arranged. You know that if you watch Downton Abbey.

‘Why you?’ John wants to know. ‘And why me?’

“Because,” Jesus answers, “in this way we do God’s will.” In this way everyone sees what God is up to. And what God is like. I go down in the river below you. You stand above me. You go one up. I go one down.

Ah! The revelation dawns. We know from the voice that speaks after the baptism that Jesus is God’s dear Son. But it’s when he submits to the baptism in the first place that we discover what kind of Son this Son of God is.

Who and what is the Son of God? He is one down, immersed in the river of human frailty and sin, turgid with tears and suffering, malice, carelessness, indifference, failure, and endless regret.

Why is God pleased with him? Because he gets into that water with us, side by side.

“Me, baptize you? God forbid,” says John. “You’re the messiah, the big shot of God. You should baptize me.”

“God forbid,” say all of us who spend most of our lives doing everything we know how to get ahead, climb the ladder, be somebody, go one up.

“God forbid,” say we all, who fear being one down like we fear quicksand and the dark.

“God forbid,” says everyone who expects their god to act like one and lord it over the cosmos.

“No,” Jesus says, “we’ll do things God’s way. I’ll go down. With you. Where you are. In the deep where all your hard stuff is swirling around. Where there’s the danger you could drown, danger you could get lost, danger you could succumb to your despair. That’s where I’ll go, a sibling in your own flesh. That’s where I’ll always be. That’s how you’ll know that God is not against you. That’s how you’ll know you’re not alone.”

And so, Matthew’s story says, John consented, and Jesus was baptized.

There’s another story in another gospel that sounds a lot like this one. We read it on Maundy Thursday. Jesus gets up from the table, pours water into a basin, and wraps a towel around his waist. Then, on his knees, he moves from one foot to the next, washing the dirt away.

He comes to Peter. Peter recoils. He tries to prevent Jesus from washing his feet. “Wash me? Not you! Get up! You’ll never wash my feet.”

Peter’s frantic with embarrassment. Jesus is the Teacher, the Lord. Peter is the follower, the idiot disciple. This isn’t proper. It should be the other way around. Peter watches Downton, too.

But Jesus says to him, “If I don’t wash you, you won’t have a place with me.” If you don’t let me serve you, you won’t know me, or God. If you insist on proprieties, you’ll miss the gospel. If I don’t kneel before you, you may never know the converting grace of love.

And so, the story says Peter consented and let Jesus wash him.

‘The King and I’ is an old, dated movie. I’m showing my age just by mentioning it. And you’re showing yours if you remember it. But there’s a scene in that movie in which Anna, the English governess of the Siamese king’s children, learns the protocol for being in the royal presence. No one’s head must ever be higher than the king’s. If he’s in the room and you’re taller than he is, you have to stoop or lower your head so that his remains higher.

The king enters the room. Anna lowers her head. Then playfully—but also to show that he can—he lowers his. She lowers hers again. He stoops down. She stoops even lower. Finally he drops to his knees, and she has to go flat out on the floor. The point is made.

But now imagine that scene the other way around. Imagine a completely new protocol—the king has to go one down. No one’s head can be lower than his. He’s the one who ends up prostrate before the governess.

This is Jesus.

And this is his God.

Over the centuries, a great many Christians have been embarrassed by this revelation, put off and dismayed by a God who stands in the sinners’ line, who bathes in our messes and kneels at our feet. We’re always trying to turn the one down God into a one up God, and when we do, we justify all sorts of pompous nonsense and bloody mayhem in the name of God’s one up-ness.

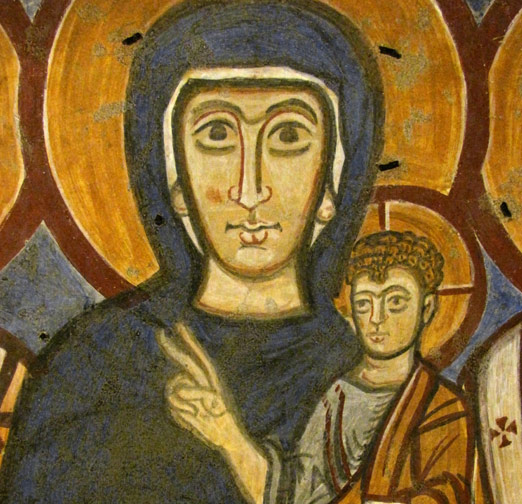

But sometimes, some blessed times, we’ve managed to love the one down God. We’ve let ourselves be drawn to the sweetness of Christ’s humility, swept up in his kindness, his refusal to lord it over us, his eyes that look up at us and not down.

The have-nots have never had much trouble loving him, but even some privileged and powerful people have fallen hard for his humble, hidden majesty. And when they have, they’ve found themselves in the Jordan, over their heads in human empathy and solidarity, immersed in a mystifying kind of joy.

I think of Francis of Assisi, the dissolute son of a wealthy merchant. He had an epiphany about the one down-ness of God while he was gazing at the figure of the abandoned Christ on the cross. It took Francis a long time—don’t believe all that medieval nonsense about instantaneous conversions—but eventually he fell in love with the poor and humble Christ. And out of that powerful attraction, he began giving away everything he had, and most of what his father had too.

This profligacy did not endear him to his proud and influential father, who was apoplectic at the sight of his privileged son one down among the leprous poor. But Francis was smitten by them. He ended up a beggar among the beggars, a disowned and displaced man. He waded into the Jordan with Jesus and never looked back.

Not everyone who’s attracted to the one down Jesus ends up disowned and begging like Francis. His is not the only way. Your heart can be broken open and your life re-humanized by the revelation of God’s humility in all sorts of ways. We each have to find our own path downward, as individual disciples and as a community of disciples. But one thing is true for everybody—if we feel even the slightest attraction to the one down God, sooner or later we’ll find ourselves in some discomfort, torn between the life we have now and the joy we sense is waiting for us under the river with him.

I once had a testy discussion with a woman new to our church about the foot-washing that was part of our Maundy Thursday service. She was aghast at the thought of it. “Why do you do such a weird, uncomfortable thing in this day and age?” she wanted to know. “We don’t wear sandals. Our feet don’t get dirty and need washing like they did in Jesus’ day.” Apparently she’d never distributed clean socks to homeless people. When she said ‘our feet’ she meant the clean healthy feet of people like her. “Furthermore,” she declared, “foot-washing is unhygienic, awkward, servile, and embarrassing.”

I said, “Your point?”

She said, ‘Well, all I know is you’re not touching my feet.’

But she surprised me. And maybe herself. She showed up, got her feet washed, and washed other people’s feet, too. Later, she confessed to a deacon that she’d wept when one of the oldest members of the congregation got down on his knees kind of creakily to dry her feet. She also confessed she’d gotten a pedicure earlier in the day. I guess foot-washing is more tolerable if your feet look good. I guess you can go one down as long as your feet are still one up.

But I’m not knocking her, believe me. It wasn’t a small thing for her to dip her beautifully lacquered toes into the Jordan with Jesus. Even a faint light in a great darkness is light. Even a slight unveiling can illumine the world, and maybe save it.

It was something big, her timid embrace of the distinguishing mark of a disciple: kneeling, one down. It was something, her beginner’s acceptance of the inescapable paradox of Christian faith: down is glory, lowliness is joy, embarrassment is glory. It was something, that start, that little falling in love, that little baptism, that epiphany.

And on this day of Jesus’ baptism, I wish something like that for us all.