Our Christian ancestors who invented Advent believed that following Jesus is an arduous vocation, easily abandoned when life gets tough, and even more easily abandoned when life gets really good. In both cases, they knew that we’d be tempted to deposit our human hope in things that are more immediately alluring than the Lord who left us long ago for a seat at God’s right hand. They knew that we would settle for living “ordinarily”—we would eat, drink, make merry, get and spend, marry and give in marriage oblivious to the deeper currents of God’s activity in creation, eventually losing ourselves in self-concern.

We would, they knew, get tired and bored and doubtful about the whole Christian enterprise. We would sleepwalk through our lives, waking up only briefly at times of wrenching loss or personal danger. At those motivating junctures, we might swear to live more attentively, and perhaps for a while we would let ourselves test the sharp edges of a life of faith. But it would not be long before we’d slink back to our warm beds, not long before we’d nod off again over our detective novels. We would forget who we are, where we are going, with whom we are traveling on the Way, and who it is who will come back for us when all is said and done.

And this is why those forbears of ours decided that Advent should begin with The End. Every year, the scripture appointed for the first Sunday of the season fast-forwards us to a vision of The Last Day. “Look hard at this spectacle,” the texts demand, “and see the way history ends, Jesus returns, the good are rewarded, the wicked are punished, and everything that is wrong with the world is set right. Take a lesson from this. Wake up. Live attentively. Take heart.”

These readings are traditionally drawn from texts that whack us in the face with crisis, warning, denunciation, cataclysm and judgment. It’s a genre called ‘apocalyptic’, and it plunges us into the middle of a roiling imaginative universe where angelic armies battle Satan’s minions in the ultimate cosmic smackdown. Blood drenches the moon, stars and planets explode out of their orbits, and darkness descends upon an earth laid waste by pestilence and earthquake, fire and sword. Apocalyptic is not demure about getting its message across.

Don’t waste time, it exhorts, for time is short. Shorter than you or anybody thinks. There is an end to everything, injustice is not forever, things will be straightened out once and for all. It won’t be pretty, it won’t be easy, but it will come to pass. God is in control. Therefore, do not be dismayed by the success of the wicked, much less secretly hope to enjoy that success for yourselves. Don’t be alarmed by the violent domination of the vulnerable by the strong, much less secretly covet their power. Don’t be distressed by the sleek lives of the rich, much less envy their horse farms in Virginia and easy access to Botox. They will not always come out on top. The victim will not always be victimized. A glorious reversal of fortune for the innocent, the poor and the weak is in the cards. You will see it! Hope, and keep on hoping. Wait, and keep on waiting. Be alert, and stay that way.

Easier said than done. As preacher Robin Myers writes, “life itself passes daily judgment on the idea that [God is in control], that good deeds and righteous living exempt us from mindless tragedy, or that the meek will inherit anything other than a crushing debt and a dead planet.” Nonetheless, and hoping against hope, today’s scriptures emphatically encourage us to stand firm, to refuse to throw in the towel. God really is in charge, they assert, and one day you won’t have to take that on faith.

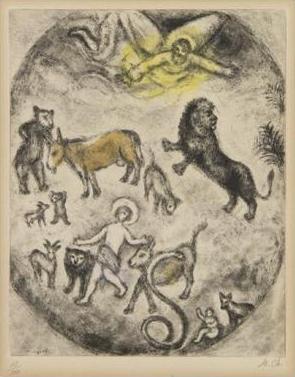

Biblical apocalyptic paints a very big picture for the myopic Christian. It reveals the Scene behind the scene, and for faithful people it’s a good one in the end. For the faithful, the end-time’s chaos and terror are not a prelude to eternal destruction as they are for the wicked. They are birth pangs. After a long hard labor, the new age will arrive, kicking, pink, healthy, and strong. Thus the first Sunday of Advent intends to make a preemptive strike on despair as the church sets out on another year of following Christ from manger to grave, and beyond.

Quite a picture, and quite a promise! But not everybody is comforted or encouraged by it. It’s so over the top that it’s a little hard to take seriously. Its images are bizarre and off-putting, its symbolic world almost impenetrable, its action often martial and bloody. One could be pardoned for entertaining some serious theological qualms about this apocalyptic vision, questions about the way it sizes up the human condition and God’s response to it.

Whatever we may think about the Second Coming of Christ, however, most of us here today would likely agree that if he is really going to return some day, any importance this event may hold for us now does not reside in the minute details of how it might unfold then. We don’t think that in order to be a faithful disciple you have to believe in every last one of its predicted particulars.

But some Christians do think it matters. It matters infinitely, decisively, and so they dedicate themselves to a zealous study of that ‘day and hour.’ No matter how often they read in the Bible that it’s impossible for anyone, not even Jesus, to know God’s calendar; no matter how many times Jesus says not to dwell on or get anxious about what might happen at The End, but to serve the neighbor humbly in the meanwhile; no matter how repeatedly the Bible insists that judgment, reward and punishment are to be left solely to the mysterious discretion of a merciful God, they don’t think these admonitions are meant for them. And so they persist, removing this apocalyptic and prophetic end-of-the-world/Second Coming stuff from where it resides at the periphery of the Bible’s deepest concerns, and moving it right to the center.

They take it all literally, too, despite all kinds of indications in Scripture itself that we’re not supposed to. They work their spiritual slide rules overtime to determine to the millisecond when the prophesied mayhem and glorious Return will occur. Matthew’s fanciful turn of phrase about the saved wafting up to meet the Lord ‘in the air’ prompts them to plot flight paths and calculate orbits. Defenseless poetic images are routinely harmed in the making of their end-time movies.

And then there are end-time movies. And books. And t-shirts. And action figures. Even a video game. For only $39.95 and a little manual dexterity, you can join Christ’s well-armed angelic army on judgment day and mow down as many of God’s enemies as you can manage to locate through the thick smoke rising from the bodies of burning homosexuals and women who have had abortions.

They preach to millions of souls on TV as well, spinning out without irony all sorts of stomach-turning scenarios based on their findings. “We want you to be saved,” they say. “That’s why we are not sparing you the gruesome reality of the fate that awaits the unrepentant.” For our own good they lay it all out for us, down to the last bloody detail of the final cosmic war. But the glint in the eye, the suggestion of glee that’s evident when well-coiffed preachers say these things belies that high-minded intention.

When I listen to them, as I sometimes do, it seems to me that this is really not about saving souls. It’s about settling scores. It’s about what it’s like to know that you know. It’s about the rush of righteousness and the sense of satisfaction that comes over you when you know that on God’s behalf you are licensed to kill—even imaginatively—every person on earth who does not conform to your convictions. It’s about maintaining the illusion of your own innocence as you search and destroy.

But more than anything else, it’s a sick fascination with violence as an instrument of divine justice. It’s a way of reading scripture that’s got swagger and virility and moral clarity. And it is completely without apology. The Second Coming justifies a kind of bloodlust, and there are Christians in this world whose various anxieties and fears have got them fixated on it. Fear, as Anthony Froude once said, has made them cruel. And it’s hard to resist thinking that that cruelty would play itself out for real, if the chance to unleash it came along.

Preacher Fred Craddock once suggested that perhaps the reason that end-time devotees are so fixated on the Second Coming is because they are secretly so disappointed in the first one. Maybe they relish the swashbuckling triumphalism, the martial adrenalin surge, the in-your-face vindictiveness of the way they read the Second Coming because the first one was so wimpy, so peaceful, so meek. Maybe they are so comfortable with the idea that the highway to the Kingdom of God necessarily runs through pools of other people’s blood because they are deep-down ashamed that Jesus never raised a fist or a sword to convince, convert, coerce or punish anybody. He did not defend himself like a man, and he didn’t allow anyone else to defend him either. Maybe they can’t fathom how the Son of God got himself killed as a sinner and an outlaw, and they need to make up for this ancient embarrassment by turning him into a vengeful, contemptuous conquering hero-action figure at The End.

Let me now give these already-much-maligned end-time fanatics a rest, and lay all my cards on the table. I don’t think it’s only fundamentalist end-time fanatics who are mortified by the ineffectual First Coming of Christ. Very few of us really want Jesus to be the meek and humble Lamb of God and the non-violent Prince of Peace. In theory, maybe, but not for real. It’s okay to talk like that while he’s a baby, but we get impatient with his habitual mildness when he’s all grown up. Preacher Will Willimon has this to say about our impatience:

Of course we know that… Jesus’ way was love, justice, and other sweet spiritualities. But sometimes you have to be realistic, to forget all that and take matters in hand… I remember armchair campus liberation theologians who, while not thinking that violence was a good idea, particularly violence worked by the state, thought that the violence worked by Sandinista revolutionaries on behalf of the poor was OK. Violence is wrong—unless it is in the interest of justice, which makes it right. During the last Presidential election, there was debate about Senator Liebermann. “He’s a devout Jew,” some said. “He keeps Kosher. If we have a national crisis and need to go to war on a Saturday, could we count on Liebermann?” Nobody said, “George Bush is a Methodist, Al Gore is a Baptist, don’t these Christians have some funny ideas about non-violence? Can we count on them to kick butt when we need it?” Nobody asked because, well, when it comes to such issues, you can’t tell the worshippers of Caesar from the devotees of Jesus… Relying on the power of God is fine, but just in case that doesn’t work out, keep a couple of Smith and Wessons in the glove compartment.

The lamb will indeed lie down with the lion when the Kingdom comes, but, as someone once quipped, if the dear little thing has half a brain, she’ll keep one eye open as she sleeps. Never mind that on the very night the soldiers came for him in the garden, Jesus commanded us to put away our swords. In this day and age, it is naïve and unrealistic to do anything like that.

Advent is here, and the texts of the first Sunday point us to the end of time. Perhaps the apocalyptic character of this end is hard to swallow, and if that’s the case for you, let me suggest that we just get over it and stop worrying about it, and focus our attention instead on another kind of end. How about we put an end this Advent to the idea that violence—all violence, and especially holy violence—just happens; that it’s just one more of those ‘human nature’ disabilities we are never going to get rid of, so we might as well give in and participate? Let’s end the idea that although nobody really wants it, violence just gets thrust on us, and it’s ‘naive and unrealistic’ to refuse to respond in kind. You have to set out to make a sword; it must be forged on purpose, and it is sweaty labor. Someone decides to make a bomb; it costs a lot of money. You have to want to do it. Swords do not spring naturally from the earth like gladioli. Bombs do not hang from trees like lemons and figs. We choose them. We study war. It is no accident that swords and plowshares—instruments of war and implements of food production—are mentioned in the same breath in our reading from Isaiah today. Every sword and bomb we make takes food from the poor and the hungry. We know that this is true, we know the costs and consequences, so how about ending our sleepwalking denial about it?

And while we are talking about the end in Advent, let’s put an end to the idea that only Jesus, because he was perfect, or because he is ‘God’, could do the peaceful things he preached. That his peaceful way is beyond our human capacity. Let’s put an end to the assumption that he sets beautiful but impossible ideals for his followers, ideals we therefore are not obliged to attain, which usually means we don’t even try. An end to our subtle equivocations about the gospel. And an end to our unacknowledged shame that we are waiting for a savior who can’t save us at all—at least not in the way we’d love to be saved, with guns blazing and our enemies writhing under his feet.

Advent is here, dear church, and the first Sunday points us to the end of things. If it is true that Jesus is coming back for us some day, then along with the whole church let’s rejoice and be glad. Let’s join our hearts to the deep, plaintive longing of the ages for the universal justice that will finally be installed some great and glorious Day. Let’s be happy if then, at last, the world comes to know Christ as the One on whom God’s favor rests in a unique and awesome way. But whatever else we do, let’s not miss him here and now in the meanwhile. Here, where he lives meekly alongside the very sinners that too many Christians want to kill. Now, when he still means what he has always said to us, “Peace be with you. Now, put away your swords.”