In addition to four Sunday Advent services, many Christian congregations offer an extra service in the weeks leading up to Christmas. “Blue Christmas” services (as they are commonly called) came onto the Protestant liturgical scene in the mid-1990’s in pastoral consideration of the sadness, depression, loss, and estrangement many people report experiencing during a season of relentless cheer and family-centered celebrations. Normally held in the evening in mid-to-late Advent, these services are designed to acknowledge this pain and offer consolation in the form of worship that does not take for granted that all is well.

By many accounts, Blue Christmas services succeed beautifully in this aim. Many friends and acquaintances—and pastoral colleagues— express sincere gratitude that there is, as one put it, “a safe and sacred space” for people to name their sense of alienation or sadness, and to do so in the company of others whose experience of the season is similar. Blue Christmas services, they testify, more or less save their lives every year. I believe them. I’ve been to a few myself and can testify to their impact. All the same, I always feel an odd twinge of disappointment when the announcements of Blue Christmas services start popping up in church bulletins and on Facebook. There’s something about them, or perhaps better said, the fact that we do them, that gives me pause.

It’s hard to put my finger on the reasons for this niggling discomfort. Maybe it has to do with the way we have so quickly come to accept these services as the best or (dare I say?) the right way to address the pastoral situation that prompts them. There’s not been very much theological or liturgical reflection about Blue Christmas, other than the assertion that it serves a need. I don’t mean to imply that additional reflection will lead to a different conclusion; I mean to say only that whenever an innovation arises in the church—whether in doctrine, practice, or liturgy—it is worthy of reflection.

Change and innovation always offer gifts (which is why a lot of innovation-minded pastors keep telling their reluctant people that they should happily embrace them); but they often also offer some loss. It seems to me that the church should want to understand as clearly as it can what it stands to gain from an innovation, and what it might stand to lose.

I want to reflect on the “lose” part of this equation, not (I repeat) because I feel negatively towards Blue Christmas services, but because I think the “gain” part has already been articulated, perhaps not so much in theological essays or pastoral sermons, but in the sheer proliferation of these events. The faithful (and many seekers) have voted with their solace-seeking feet, and the verdict is in. It’s a gift to the church to be prompted to name and embrace a more nuanced and compassionate understanding of the human predicament in the seasons of Advent and Christmas. It’s of benefit to the church to ritualize a divine-human encounter that does not flinch from our weaknesses, thereby creating conditions of possibility for God’s grace to reach, comfort, encourage, and heal our broken hearts.

There are, however, critical questions that arise from the Blue Christmas phenomenon. Here’s one that comes up for me: I wonder if the proliferation of such services in Advent casts doubt on the liturgical adequacy of Advent itself, at least as the season is currently observed in many mainline Protestant churches. What is lacking in the Advent liturgy or the way we perform it that allows people to conclude that it isn’t designed to handle sorrow and loss? What does this say about our own assumptions about what the tone and content of our regular liturgy should be? What we are doing that makes it necessary to create new liturgy for the sole purpose of helping people in need of consolation and support navigate their loss and grief? Why are we steering people away, in a sense, from ordinary communal prayer and segregating their pain in separate services designed solely (or at least primarily) for the hurting?

There are, however, critical questions that arise from the Blue Christmas phenomenon. Here’s one that comes up for me: I wonder if the proliferation of such services in Advent casts doubt on the liturgical adequacy of Advent itself, at least as the season is currently observed in many mainline Protestant churches. What is lacking in the Advent liturgy or the way we perform it that allows people to conclude that it isn’t designed to handle sorrow and loss? What does this say about our own assumptions about what the tone and content of our regular liturgy should be? What we are doing that makes it necessary to create new liturgy for the sole purpose of helping people in need of consolation and support navigate their loss and grief? Why are we steering people away, in a sense, from ordinary communal prayer and segregating their pain in separate services designed solely (or at least primarily) for the hurting?

In other words, are Blue Christmas services a sign of the failure of Advent and Christmas worship to address the full scope of human experience? Why doesn’t regular worship do for people what a special service appears to do?

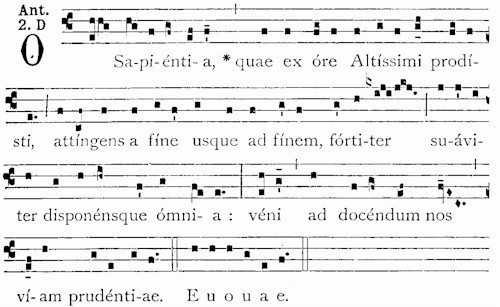

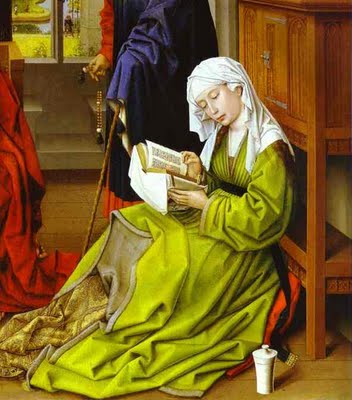

If it turns out that our performance of the ordinary liturgy really is failing a significant segment of people, this is an important datum, and not a good one, because the Advent/Christmas cycle is aimed precisely at accommodating, embracing, comforting, reassuring, and reorienting a human race that has grown alienated from the source of its deepest joys. Through its classic texts, hymns, and prayers, it intends to move us all to face squarely the painful paradoxes of our human condition, the dashed hopes and deep fears of all the years, the grief of our losses and the tangle of our sins; and to clear an attentive compassionate and hopeful space for us to perceive a cry in the wilderness, lift our hearts to the footfall of a messenger on the mountain, and be charmed into new life by a lullaby of love and praise cooed over a newborn by a mother who has already had her fair share of losses, and will soon suffer even more.

The whole Advent/Christmas story is something of a downer, with its consciousness of lack and estrangement, its longing across seemingly unbridgeable distances, its village scandals, its particular hardships—occupation, cruelty, rejection, homelessness, poverty, infanticide and the kind of ageless grieving “that will not be comforted.” From this standpoint, every Advent and Christmas service is blue—and liturgically designed to make us face and negotiate the dislocations and fragmentations of life in frail and wounded flesh, as well as to find ourselves approached, embraced and remade by One who is coming, a fellow-sufferer who knows from the inside what we are made of, and whose compassion, therefore, is infinite, and infinitely healing.[i

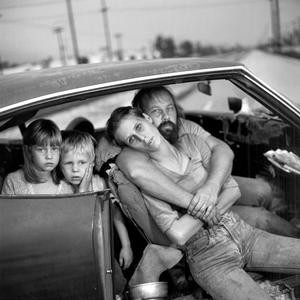

If this is not the sort of liturgical encounter people are being invited into on Advent Sundays; if we have been playing down or obscuring the heartrending aspects of Advent and Christmas, cutting away its reference points of sin, pain, grief, and loss as if they were the unwelcome face of an ex-spouse in an old family photo; if we are reluctant to engage the very particular forms of human suffering the liturgy names in this season, in favor of focusing on the generic “wonder of children” (whose childish excitement then serves to circumscribe the range of acceptable emotional responses to the season), or on the warmth of family and friends, or on the cute pageant and the big anthem; if we eschew the telling human detail in favor of four weeks of universal (and often vague) concepts—hope, peace, joy, love—it’s no wonder that the woman whose husband just walked out on her, the young adult estranged from his family over his sexuality, or the 80-something fellow whose siblings and friends are dying off faster than he ever thought possible don’t dare weep in the back pew on Sundays, but decide to show up at a special Blue Christmas service instead, so that they can be who they are, feel what they feel, and sit with others who feel odd and out of joint not only in the mall, but also in the pews of their home congregations during the Advent and Christmas observance.

If this is not the sort of liturgical encounter people are being invited into on Advent Sundays; if we have been playing down or obscuring the heartrending aspects of Advent and Christmas, cutting away its reference points of sin, pain, grief, and loss as if they were the unwelcome face of an ex-spouse in an old family photo; if we are reluctant to engage the very particular forms of human suffering the liturgy names in this season, in favor of focusing on the generic “wonder of children” (whose childish excitement then serves to circumscribe the range of acceptable emotional responses to the season), or on the warmth of family and friends, or on the cute pageant and the big anthem; if we eschew the telling human detail in favor of four weeks of universal (and often vague) concepts—hope, peace, joy, love—it’s no wonder that the woman whose husband just walked out on her, the young adult estranged from his family over his sexuality, or the 80-something fellow whose siblings and friends are dying off faster than he ever thought possible don’t dare weep in the back pew on Sundays, but decide to show up at a special Blue Christmas service instead, so that they can be who they are, feel what they feel, and sit with others who feel odd and out of joint not only in the mall, but also in the pews of their home congregations during the Advent and Christmas observance.

I am not suggesting that we turn Advent and Christmas Sunday morning worship services into a sallow, somber slog through every problem and pain known to humankind. There’s already enough pressure on pastors annually to produce a “perfect” Advent and Christmas that appeals, impossibly of course, to a thousand different tastes, preferences, age groups, and memories; and satisfies every conflicting and mutually exclusive felt (and loudly expressed) need. Besides, there is no quick fix for the church’s weakened liturgical sensibility (if a weakened sensibility is indeed part of the disquiet I feel and am trying to describe). Improvement will be slow and long-term, the product of ongoing reflection among pastors and people. The last thing I want to do is provoke anyone to re-think the plans for this year! I am suggesting, however, that the project of reinvesting regular worship with the tensions that make it “work” (at least potentially) for the serene and the troubled alike is a project worth shouldering—little by little, over time.

Worship that “works” for all, in season and out, requires a skillful interweaving, a sensitive rhythm if you will, of elements that affirm the best human values of culture and faith and open a space for the interrogation of those values by the gospel prayed, proclaimed, sung and confessed. This is probably way too simplistic, but for the sake of argument we might say that the ordinary liturgy of the season seems to do the happy, all is well, mythic stuff pretty well, and Blue Christmas services seem to have the sad, it isn’t all glorious, there’s another side to the story, wait a minute stuff down pat. We’d all be better off, however, if we could manage to do both in the same service, or over time in a series of services, not aiming for some phony “balance,” but in a way that mirrors the real life oscillations of soul anguish and body anguish we human beings experience in the midst of cheer, and the gladness and gratitude we are all in fact capable of knowing, even if it’s hard, in the midst of our pain. If we have lost this deft touch when it comes to creating worship that takes us on such an honest journey (liturgical scholars refers to it as the interplay of the “mythic” and the “parabolic”), we need to figure out how to recover it.

I like Blue Christmas services, but beyond their immediate usefulness to those who attend them, I wonder if they might have a more bracing purpose. Maybe they could serve as smelling salts for the liturgical practice of the churches. Maybe they could get us to wake up to the season’s inherent possibilities and draw out from our worship the full range of its concerns so that we will eventually have no need for extra services that make it too painfully apparent that right now, anyway, there is no room in the ordinary liturgical inn for the real hard griefs of real hurting people. The recovery of the ordinary liturgy’s intentions to be that welcoming house might someday reveal that the genius of Blue Christmas services, the key to their effectiveness, was not so much that they were new, but that they were old—they recovered a truth that ordinary Advent and Christmas Sunday worship had discarded, and bequeathed it back.

I like Blue Christmas services, but beyond their immediate usefulness to those who attend them, I wonder if they might have a more bracing purpose. Maybe they could serve as smelling salts for the liturgical practice of the churches. Maybe they could get us to wake up to the season’s inherent possibilities and draw out from our worship the full range of its concerns so that we will eventually have no need for extra services that make it too painfully apparent that right now, anyway, there is no room in the ordinary liturgical inn for the real hard griefs of real hurting people. The recovery of the ordinary liturgy’s intentions to be that welcoming house might someday reveal that the genius of Blue Christmas services, the key to their effectiveness, was not so much that they were new, but that they were old—they recovered a truth that ordinary Advent and Christmas Sunday worship had discarded, and bequeathed it back.

They recover a truth, but not every truth. Here’s another question I have about Blue Christmas services, returning to an assertion I made much earlier about separating the hurting out. Is there a sense in which providing Blue Christmas services steers people in distress away from the church’s ordinary communal prayer and segregates their pain in separate services designed for the hurting? If so, I find it ironic and worrisome, not because people do not need and deserve to have that pain honored and their grief supported during a time when everyone is busy throwing glitter over everything that smacks of trouble; but because the way Christians have always done this honoring and supporting of each other most effectively is indeed in community—but not in communities only of the hurting. The community in which support, consolation, and healing come to each of us most surely and most graciously is the whole community, the gathering of the joyous and the afflicted, the peaceful and the troubled, the faith-filled and the faith-emptied.

One vocation of the ordinary congregation it is to model a kind of wholeness not constituted by perfection, but by sharing, by the carrying of each other’s burdens, the carrying of each other’s ability or inability to believe and to respond, and even to feel; all of us learning to regard with awe, reverence, mercy, and compassion those among us who pray with empty hands. If those empty hands feel in any way ‘disappeared” or banished by congregations that can’t bear their presence in a supposedly happy season, Blue Christmas services may only help us evade a problem much bigger and more serious than seasonal disaffection.

It’s not for nothing that “Comfort, comfort ye my people, says the Lord,” is one of the most ringing liturgical refrains of the season. Iniquity is pardoned, warfare ended, alienation cured, grief and loss consoled, a promise of healing delivered to every broken heart. This is personal, but it’s more than personal: it’s first, last, and always communal. It is about you and me in our particular circumstances, but it isn’t just about you or me and our particular circumstances. If we treat people with seasonal distress solely as individuals with a peculiar individual problem, and not also as, in some deep sense, “common” folk with a common condition, one in which to some degree we all participate by virtue of our humanity, we may miss an opportunity for solidarity of the best kind. One of the greatest gifts and truths of Christian proclamation is that if we are made whole it is because we are inserted in a whole community, because we are together, all of us: we all require healing, and the healing of one is the healing of all.

Do we assume that the grieving can be consoled only by others who are similarly grieving, in their exact same condition? Is there relief only in the company of the like-minded or the similarly afflicted? The therapeutic tradition seems to say so, but the Christian tradition has never believed this to be true; indeed, if you credit Paul, it was precisely so that all barriers between us might fall and so that tribalism might give way to communion (even emotional and psychological tribalism) that Jesus was willing to accept death, even death on a cross. Segregating hurting people may be (certainly is) helpful, good, and necessary for a time; but it is not sufficient, it does not mature our congregational life, and it should not be our only response to the problem. In the long run, it may even add an extra burden of unnecessary isolation to the burden people are already carrying.

What a grace it would be for our Christian journey if in addition to dedicating time, creativity and pastoral sensitivity to the creation of these ancillary services, we also began the equally demanding pastoral work of shoring up the deep communal character of the season and helping all our people, the joyous and the afflicted, see themselves as engaging it in each other’s company, lending one another joy and hope, solidarity and consolation, depth and sobriety, moving through this complex time arm in arm with one another’s sorrows and joys.

What a grace it would be for our Christian journey if in addition to dedicating time, creativity and pastoral sensitivity to the creation of these ancillary services, we also began the equally demanding pastoral work of shoring up the deep communal character of the season and helping all our people, the joyous and the afflicted, see themselves as engaging it in each other’s company, lending one another joy and hope, solidarity and consolation, depth and sobriety, moving through this complex time arm in arm with one another’s sorrows and joys.

I have many other questions about Blue Christmas services— e. g., Why are they invariably described as “powerful”? Is it because it’s at night and you get make things dark enough to light candles, and everybody loves candles and is moved by candlelight? Is it all “atmosphere”? If it is all or mostly atmosphere, is it also mostly emotion, and if so, will the benefits of this service stick, or will they go the way of most emotions? If we know how to do Blue Christmas services effectively, beautifully, deeply, with liturgical creativity and care—and apparently we do—why don’t we know how to do regular Advent and Christmas this way too? (Maybe we do, and I’m just being grouchy.) Are Blue Christmas services contributing, like self-fulfilling prophecies, to the need for Blue Christmas services? Are we in any way marketing sadness at Christmas? Is there a way compassionately and sensitively to help people develop disciplines of joy and gratitude through the observance of Advent and Christmas that will not mask, diminish or dishonor their loss and grief but anchor them in a truth more enduring and encompassing so that they can open themselves more fully to the One who comes “with healing in his wings”?—but I leave these questions and all the rest I’ve mused about here to your continued consideration—after the New Year and Epiphany!

Just trying to start a conversation. There’s plenty of time. And that’s all I got on my end of it, for now!

[i] Even on the third Sunday when the candle is pink and the admonition is to rejoice, there’s plenty of blue. Yes, we are told to rejoice, andto rejoice always, but that can mean only one thing—in good times and bad. The regular Advent liturgy is not oblivious to the fact that many people find cheerfulness nearly impossible in the Advent and Christmas seasons, or in any season for that matter, but wisdom is at work here. Precisely because we may lack the ability to feel cheer, the liturgy enjoins something different upon us—joy. Joy does not require that we feel or emote; it’s a gift and a virtue, available by grace and through practice to souls centered and un-centered alike. It arises not from external circumstances, but from the exercise of faith in the nearness of the Lord, whose approach makes the mountains clap their hands. (There are, of course, exceptions—a person who is deeply depressed or suicidal or suffering the first throes of a terrible grief will not likely be able to access the deepest reaches of the soul where joy resides, unaltered by circumstance. The regular Sunday liturgy nay not do much to accommodate their pain; it’s also unlikely that such grievously suffering folks will be comforted by a Blue Christmas service. Their predicament requires directed professional attention and support.)