NOTE: In March 2013, I posted a series of Facebook Notes about so-called “Christian Seders” and the special obligation Christians have in Lent and Holy Week especially to be vigilant about the way our observances may have an impact on Jews, Christian understandings of Judaism, and related matters. I have been asked by several colleagues to re-post these reflections this year. I am happy to do so. I need to make it clear, however, that I am not an expert on these matters. What I say below is my take on controverted questions, born mostly of my own reading and of my interfaith relationships. Please take them as such.

NOTE: In March 2013, I posted a series of Facebook Notes about so-called “Christian Seders” and the special obligation Christians have in Lent and Holy Week especially to be vigilant about the way our observances may have an impact on Jews, Christian understandings of Judaism, and related matters. I have been asked by several colleagues to re-post these reflections this year. I am happy to do so. I need to make it clear, however, that I am not an expert on these matters. What I say below is my take on controverted questions, born mostly of my own reading and of my interfaith relationships. Please take them as such.

No “Christian Seders,” Please!

With Holy Week on the horizon, many Christian congregations have started announcing “Christian Seder” meals to observe Maundy Thursday. People of good will recognize this as a devout and well-intentioned attempt to honor the Jewishness of Jesus, and the Jewish roots of the Christian communion meal which was, Christians say, instituted by Jesus on the night he was handed over–a night that fell, according to the gospel accounts, during the annual Passover observance. It is understandable, therefore, that Christians would desire to commemorate this institution with a nod to its original context.

There are many difficulties attaching to the practice of a Seder meal by Christians, however (the biggest being that a Seder is simply not for Christians, but we’ll get to that later). Some of them are historical. For example, we really do not know for sure what the “original context” of Jesus’ so-called Last Supper was. We think we do: since Sunday School we’ve been taught it was a Passover meal, or Seder; but scholars continue to debate the precise character of the meal Jesus shared with his disciples that night. One thing we know for sure, however, is that, although it may have been a Passover meal of some sort, it was not a Seder in the modern sense. We know this because the introduction into Jewish ritual life of the Seder we know today came generations after the time of Jesus

Modern day Jewish celebrations of the Passover are a melding of traditions that arose after the destruction of the Temple, and developed through Late Antiquity into Middle Ages. It is a still-developing tradition, too, with additions being made to the Haggadah even to this day. Ironically, some scholars believe that the modern Seder developed in part at least as a reaction and resistance to the growing influence of the Christian church and its sacred meal, the Eucharist. If that is true, Christians celebrating a Seder in the form their Jewish neighbors are using are celebrating, at least in part, a meal that was meant to criticize them and establish the distinctiveness of Jewish rites over against Christian ones. This anti-Christian critique is no longer prominent in most contemporary Seders, but this curious history of the Seder still makes for a polemical mish-mash that, if known by the organizers of “Christian “Seders, might take away some of the romance of the night!

So for starters, to hold a Seder as a way to commemorate the “background” meal Jesus shared with his disciples and which he “turned into” a Communion meal (as I have heard some Christians say) is anachronistic—it is a tradition Jesus did not know. More precisely and significantly, however, it is a tradition that developed into its present forms after Jews and Christians had taken separate religious paths. It’s a tradition, therefore, that Jews and those who became Christian never shared in the first place. It belongs to Jews only and distinguishes them as Jews in ways that make any Christian usage of it seem presumptuous, especially given the fraught and violent history of Christian usurpation and replacement of all things Jewish that we call supersessionism. Given this history and this ongoing supplanting of the Jewish covenant, I wonder if we would do better to spend our time reflecting on what often befell Jews in Holy Week in many places in medieval Western and Eastern Europe—the pogrom—than to spend time appropriating one of their characteristic rituals and making it our own.

Holding a Seder in a Christian church as a Christian event during Christian Holy Week is dicey. Dicier still is celebrating a Eucharist in the course of the Seder meal or finishing the Seder with a Communion service. This sends an unintentional but real message that the important thing about this Seder is what Jesus did to transform it and make it into something else. In other words, what we imply is that the Seder’s real value is to point towards or usher in Communion– that Communion is really what it’s all about, when all else is said and done. This is to write Jews out of their own story. We have already succeeded in often writing them out by the way we often use “Old Testament” texts in preaching and teaching—let’s not turn their meal into our meal for our devotional agendas, just because it feels more authentic or rootsy for us to do so.

Ritual is, after all, lodged in and arises from a community’s corporate experience; and in this case, it is the experience of suffering and liberation, slavery and salvation that Christian share with Jews in a kind of mythical and mystical sense, but not in fact: we are not Jews (the vast majority of us, anyway) and we cannot and do not celebrate a Seder out of anything remotely resembling the lived experience of Jews, or with the theological and spiritual worldview such experience generates. We can and must appreciate it, revere it, admire it, learn about it, even participate in it (for example, when invited into a Jewish home during Passover), but it is and never will be ours, and we ought not treat it as if it were. Just because we are a “successor tradition” doesn’t mean that everything that “they” have is or should also be ours.

There is a danger that in a well-intentioned attempt to honor the church’s Jewish origins, and (we think) do what Jesus did that night, we may end up caricaturing the Jewish ritual we claim to honor. It can be a kind of pious play-acting that is a very far cry from the profound communal anamnesis that is proper to “this night unlike any other night.” Only Jews can experience Passover in such a way that those who ate in haste and fled the Egyptians through the Sea have no spiritual advantage over those who sit at the Seder table today.

Beyond all this is the basic question of why some of us feel we need to hold a Seder in Holy Week in our Christian congregations in the first place. The treasure chest of Christian liturgical ritual that pertains to the Paschal season is so enormously rich that one wonders why we would turn to someone else’s. Perhaps it is because so few of our churches celebrate this range and depth of options that we cast around looking for something meaningful and rich like we imagine a Seder to be.

What could Christian do instead during Holy Week if we take seriously the objection that a “Christian Seder” is anachronistic, a contradiction in terms, and a potential offense to Jews today for whom the Passover rituals are a living tradition, and not a sort of curious antiquarianism?

If we really want to understand the mysteries of Jesus’ last days, we might consider participating in the classic liturgies of the Triduum, the Great Three Days of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil. It is there, in the experience of those ancient liturgical traditions that we encounter the meaning, depth, and power of our salvation. In the rituals associated with Passover, Jews recount their story of redemption. In the liturgies of the Great Three Days, and especially in the Easter Vigil, Christians recount and relive our own.

In the end, congregations that hold “Christian Seders” may simply desire to learn about Judaism, better understand their Jewish neighbors, and grapple with the Jewish roots of Christianity—all of which is commendable, even urgent. They should go ahead and do so, not with a Christianized Seder, but with a visit to their local synagogue for a talk with the Rabbi about how best to facilitate that understanding with respect. Perhaps the Rabbi would come and talk to a group in that congregation about what a Seder entails and what it means to Jews. Or perhaps a Jewish friend might have an extra place at their Seder table for some folks from the Christian congregation this year.

And if Maundy Thursday still cries out for a meal, hold a potluck, an agape meal, a love feast, an elaborated Communion service—choose from the Christian repertoire of feasts to celebrate with— but let the Jews have their feast. No Christian Seders, please!

More on “Christian Seders”

At the risk of overdoing it (I am not in fact persuaded that we can ever overdo this), I want to add to my previous Note about “Christan Seders” the following precision:

On Maundy Thursday, many Christian congregations hold “Christian Seders” in conjunction with Tenebrae, Holy Communion, and other liturgical commemorations of the night Jesus was handed over. They give various reasons for doing so, but in general they use the Seder as a way to recall and explore the Jewish roots of our faith, to honor the Jewishness of Jesus, to lend historical context to the institution of the Christian Eucharist, and to learn about Jewish ritual practices (i. e., “teaching Seders”) in an open, interfaith spirit.

In some cases, these Seders are led by Jews—a local rabbi, or Jewish friends of the congregation—but the majority are not. They are a wholly “in-house” affair, for Christians by Christians. My objections are directed at these in-house kinds of “Christian Seder” celebrations.

Congregations that borrow or adapt the modern Jewish Seder for their own devotional purposes on Maundy Thursday during Holy Week need to understand that what they are doing is not a neutral act. Apart from other significant theological and historical objections that should be made to a “Christian Seder,” [see my previous “Note”] the long, violent and painful story of Christian appropriation of Judaism itself—replacement theology or ‘supersessionism’—should be enough to make us think twice about doing it.

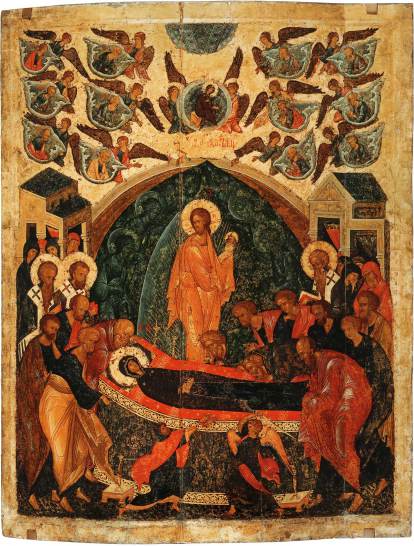

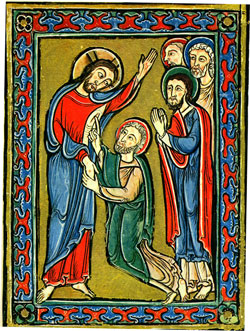

It is no accident that many a medieval pogrom erupted during Holy Week. It was a time rife with anti-Jewish preaching that placed the blame for Jesus’ death on Jews—not just on the ancient Jews, but on all Jews— and, in some cases, directly called for unsparing violence against them. Whenever Christians celebrate a “Christian Seder” that includes or culminates in Holy Communion, it is also chillingly instructive to recall that one of the great medieval slanders against the Jews is that they routinely committed sacrilege against the communion wafer in all kinds of horrific and bloodthirsty ways. This is the history we ineluctably carry with us whenever we do something like celebrate a “Christian Seder.”

My objection to the “Christian Seder” is not about the potential it has for offending Jews. It has that potential, and it does offend many Jews, and avoiding this offense is a good thing to want to do, and I do want us to avoid giving it! But the bigger issue for me is the insidious impact it can have on us Christians.

Let’s face it, despite years of interfaith efforts, many Christians continue to assume reflexively that Christianity has supplanted Judaism in God’s plan and affections. We might not say it that way, but it shows in the way we use certain biblical texts, talk about a God of Love (Christian) and a God of Wrath (the “Old Testament God”), and juxtapose Law and Grace—in these cases and others, the clear implication is that Christianity has not only succeeded Judaism, it has superseded it.

In their everyday dealings with Jews (if they have such connections), most mainline Christians probably don’t regard the religion of their neighbors, friends, and coworkers as inferior to their own; but in church, in the course of hearing scripture and sermons on scripture, during certain liturgical seasons, and in devotional conversations, an old reflex asserts itself. Our inner Marcionite emerges, and as long as no one corrects us, we continue to operate in the universe of stereotype and slander that for centuries made it possible for Christians to see it as a religious duty to defame and slaughter Jews. And the fact that we do so often unwittingly makes it all the worse.

This is my point: not only because we have a long history of appropriating Judaism for Christian ends, making of it a mere preparation for the true faith and regarding its characteristic practices as mere foreshadowings and symbols of the real things, we are still doing it today. The practice of a “Christian Seder” is a good example of just how unexamined this fraught relationship remains, and thus how easily its consequences could be visited on our neighbors again, even in our enlightened, interfaith, tolerant, and inclusive age.

That it could never happen here, that it could never happen again, that we would never do that—these are the lazy assumptions that allow us to meander through Holy Week up to our necks in the dangerous waters of supersessionism, playing out again and again the old patterns of reflex disdain.

Contempt takes many forms: I think the celebration of a Seder by Christians and for Christians for our own Christian agenda is one of them. It may seem devout and altogether benign, even constructive, on the surface; but it is just one more in a long sad line of things we have tried to steal from Jesus’ people in his name, as we have systematically written Jews out of their own story because, we say (not without truth), it is also in a deep sense our story too. And if it is also our story (and here we go wrong) we can do with it whatever we please.

Although holding a Seder (for Christians by Christians for a Christian agenda) may seem like a devout and constructive thing to do, and no doubt for many Christians it lends meaning to the Holy Week journey, it is an unavoidably fraught activity. Our anti-Jewish history has earned us a particular responsibility to make sure that our embrace of the Jewish heritage is serious, respectful, self-conscious and well-considered. We may not borrow, play-act, adapt, or otherwise appropriate anything Jewish like a Seder without carrying with us into that activity this whole history.

Remembering and telling the Jewish story is one of the Seder’s most characteristic features. Maybe instead of holding a Seder we should make time in Holy Week remembering and telling our own story, lamenting and repenting the sad history that haunts us still, and looking to Christ for the grace to change it, once and for all.

Postscript on “Christian Seders,” supersessionism, and reading Scripture

Some of you asked me to make more widely available this comment I left in a thread about the “Christian Seder” business. It concerns supersessionism and the Bible. Here it is:

I do not mean to say that we Christians cannot read texts from the Bible (”Old Testament”) and find in them Christological meaning. I think it is perfectly appropriate for us who hold (and have tenaciously held since the days of Marcion) to both ‘testaments’ as one Bible to read ‘backwards and forwards’ in this way.

Within the household of the Christian church, I believe we can own and interpret Hebrew Scripture faithfully, without contempt, even when the meaning we find in the texts is not its “original” meaning for the people who gave the world the Bible.

I don’t think it is necessarily a usurpation of a supersessionist variety for us to cherish, for example, the suffering servant text in Isaiah as having something to do with the way we think about Jesus, or the text about the young woman conceiving as having something to do with the way we think about Mary, as long as at the same time we also know that it doesn’t in fact have to do with Jesus or Mary, and that it has a meaning of its own not only for the Jews “back then,” but also for the ongoing community for whom the Book is a living testament.

What we cannot do is say ‘This (Mariological or Christolical reading) is THE meaning of the text.” We must say instead, “This is the way we (Christians) read it in the light of our religious experience and tradition.” There’s a difference, I think, between reading the ‘Old Testament’ in a Christian way and circumscribing its universe of meaning to the Christian reading.

In short, no Christian in the pew should ever come away from a sermon on the suffering servant text thinking it is a Christian passage, even if they’ve been helped to see that, while it does not refer to Christ, it can and does help us think about, know, and love him.

To avoid “writing Jews out of their own story” when we engage in a “Christian” reading of the Hebrew Scriptures, then, we need to operate on two levels at once: on the level of the text as an expression of a particular people’s religious experience, which is not ours; and on the level of the text as the Church hears it in the context of its its particular experience of Christ.

This double-vision may oblige us, for example, to refrain from a too-easy juxtaposition in liturgy of certain texts, “OT” and “NT,” that suggests that the NT text explains or fulfills the OT text in a way that exhausts all other possibilities of interpretation (this happens way too frequently in some lectionary pairings).

It may oblige us to speak of certain figures and events in the Hebrew Scriptures less as archetypes, allegories, or foreshadowings of Christ and his ministry, and more as evidence of the consistent pattern of God’s activity throughout ”salvation history,” with which our Christian experience of God in Christ is wholly consistent .

It may simply mean that we take the time to put a short note in the bulletin giving the original context of the text, or explaining the way the texts are used in, say, The Messiah or other Christian sacred music.

Before all else, however, it means that we have to spend more time as pastors, educators, leaders in and of Christian congregations helping people to love the Bible, read the Bible, and to read it with prismed glasses, since for Christians, no one lens suffices.

Of course, this is a super-challenging activity for many contemporary Christians who barely know the Bible at all any more, let alone its hermeneutical complexities, but we can’t expect anyone to read “without contempt” if we don’t teach with urgency.