–The Child Jesus with A Walking Frame, Hieronymous Bosch, 15 c.

I.

n the 1960’s, Kodak ran a commercial during “The Wonderful World of Disney” that became one of the most beloved in the history of advertising. It was a simple photo sequence that captured the progress of a baby from infancy through girlhood, adolescence, young adulthood and marriage, ending with the young woman coming home from the hospital with a baby of her own in her arms.

The pictures were accompanied by a song called, “Turn Around.” Parents everywhere blubbered openly when it played.

Where are you going my little one, little one?

Where are you going, my baby, my own?

Turn around and you’re two,

Turn around and you’re four,

Turn around and you’re a young girl

Going out of the door.

Where are you going my little one, little one?

Little pigtails and petticoats,

Where have you gone?

Turn around and you’re tiny,

Turn around and you’re grown,

Turn around and you’re a young wife

With babes of your own.*

The ad and its soundtrack were impossibly sentimental, but something about them struck a deep chord. Little ones grow up, we all know, and they do it, it seems, when you are distracted for a split second.

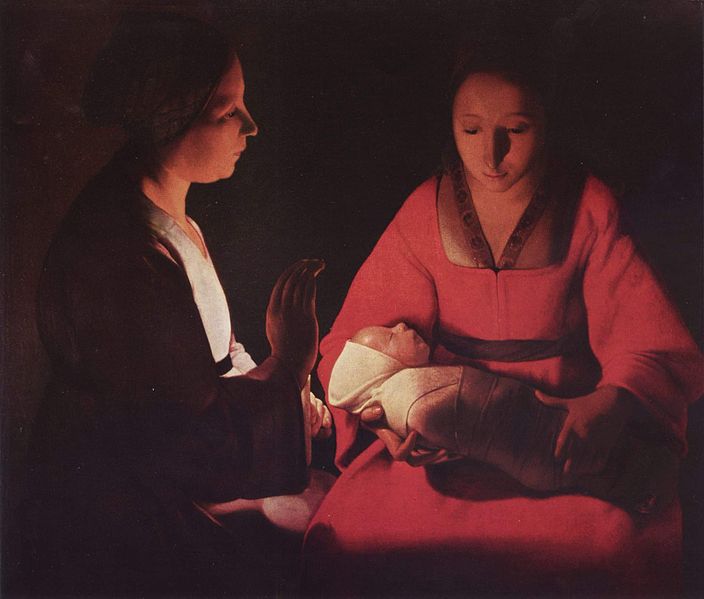

Only a week ago it was Christmas. The Babe in the manger hadn’t even opened his eyes. Last week, he wasn’t old enough for strained peas. This week he’s an adolescent. How did we get here so fast? Turn around and he’s born, turn around and he’s grown…

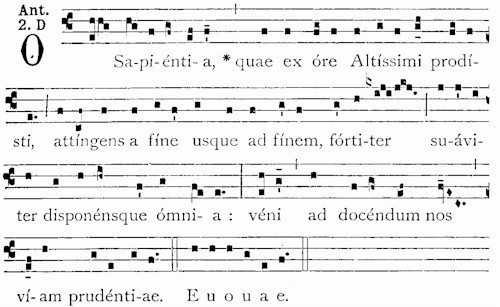

Grown, and something of a prodigy. He’s wowing the teachers in the Temple with precocious questions. He’s a willful kid too, and he’s giving his parents fits. I’m told that Luke uses the same word to describe Mary’s anguished confusion in this episode as he uses to describe the consternation of Dives, the rich man who ends up in hell in the story of the beggar, Lazarus. Luke knew something about the underbelly of parenting, I guess.

In the church I grew up in, we called this Sunday ‘Holy Family Sunday.’ It was a celebration of the ideal family, the one we were supposed to imitate in our own. I could never figure out what was so ideal about them, though. It didn’t seem very ideal to me to misplace your kid in a big crowded public place. And when his careless parents find him, Mary doesn’t seem to remember or much care that Jesus is Somebody Special. She’s as frazzled as any ordinary mother would be and yells at him as if he were a run-of-the-mill pre-teen. Jesus’ reply is curt, even dismissive. This sounded more like my own family, certainly not a holy one.

Mary doesn’t seem to remember or much care that Jesus is Somebody Special. She’s as frazzled as any ordinary mother would be and yells at him as if he were a run-of-the-mill pre-teen. Jesus’ reply is curt, even dismissive. This sounded more like my own family, certainly not a holy one.

But the preachers of my youth didn’t seem to notice. They especially played up the last line of the story—He went down with them and was subject to them. ‘Go and do likewise’ was the moral of the story, as far as they were concerned; and every parent in the sanctuary nodded in agreement while we kids slumped in our seats. The Holy Family is a family in which parents are good and caring, and their kids submissively obey them.

–Christ among The Doctors, Cataln, 14th c.

II.

Of course this is Kodak sentimentality passing for Christian instruction. Not only is this not a story about a Holy Family, it’s also not a story about being submissive. It’s a story about the time that comes when one must disobey. It pinpoints the moment when an authentic calling renders human absolutes relative. It’s a story in which we learn that sooner or later choices have to be made that override the obligations even of blood kinship.

Luke shows us this moment in Jesus’ life by playing on the word ‘father’ in the exchange between the boy and his mother. Mary asks, ‘Why have you done this to us? Your father and I have been searching…’ Jesus responds, ‘Why were you looking for me? Did you not know that I must be about my Father’s business?’ In this moment, Jesus shifts his allegiance from Joseph (‘your father’) to God (‘my Father’). This child is becoming an adult, and we know he’s on his way because he is sorting out competing loyalties; he is negotiating the tensions between ordinary expectations on the small stage of a nuclear family and great aspirations on the larger stage of a ministry to the world; he is making choices and accepting the obligation and pain that comes with a life-claiming, life-shaping call: ‘I must be about God’s work.’

Eventually Jesus will return home with his parents, for the time being, the story says, and ‘obediently.’ And then the gospels are silent about him for the next eighteen years. But the die is cast at twelve. According to Luke, Jesus was born for one purpose only, the common human purpose—to grow up; that is, to achieve an adulthood shaped around chosen priorities. Here Jesus is already clarifying what his will be—only those things pertaining to God’s house and God’s business. The priorities Jesus chooses will lead him to demand a wrenching reordering of everything. We know how that goes: The mighty cast down, the rich sent away empty; the meek inheriting the earth, the last moving into first place, mercy trumping everything else.

Jesus’ commitment to God’s work will also demand a new kind of kinship that persistently condemns the ordinary idolatry of clan and family. His first and final allegiance to God’s house over all other allegiances to every other house – personal, religious, political, national – will eventually mark him for a state execution; and in the meanwhile his own family will be embarrassed, confused, and disheartened by the things he says and the company he keeps.

But all this is in the future. It will come soon enough. In a split second of Marian distraction, he will be fully-grown. In another blink of an eye, he will be dying on a cross. But for this split second now, he is a boy, learning the Law and beginning to walk in the pathway that will be his life.

–Christ in the House of His Parents, John Everett Millais, 1849-50

III.

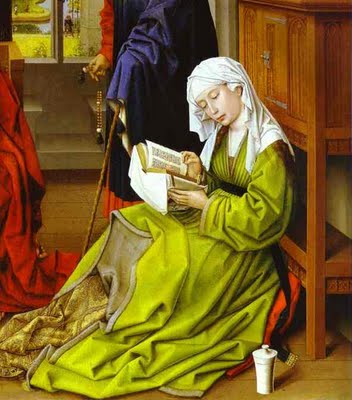

In the Christmas season, I hear many smart, faithful Christians say they don’t believe any longer in the New Testament’s infancy narratives—especially Christ’s miraculous birth from a mother who was also a virgin. As I grow older, I find these ancient stories easier and easier to believe, at least to believe in that way theologians call ‘a second naïvete.’ My problem is not with the divine child in the manger, but with the precocious, willful boy in the Temple who is figuring out that God’s business merits the unswerving dedication of a whole life. As Will Willimon once noted, it is harder to believe in a life ‘unreservedly shaped around the priority of God’ than it is to imagine that a virgin could bear a son. It’s not that hard to embrace the possibility that God came as a human baby if God stays a baby and does not grow up to be a man who is God’s alone, and does not demand that we choose to be God’s too.

Former UCC General Minister and President, John Thomas, tells this story:

“Bethlehem, Pa., was named by its Moravian founders after their first communion service was held on Christmas Eve. Today ‘the Christmas City’ offers a delightful array of Moravian Christmas traditions [to the public] every year… [Annually], a Nativity scene is erected on the plaza between the library and city hall, dominated by a huge lighted star on the mountain overlooking the Lehigh River to the south.”

One year, John continues, while he was serving a church in nearby Easton, “the newspaper reported that the figure of Jesus had been stolen. Jesus was eventually located… where the vandals had left him and, to avoid a recurrence, the city mothers and fathers bolted him to the manger after they returned him to the plaza.”

Most of us, as John comments, are “happy to keep Jesus bolted to his manger.” Who wants him grown up and walking around, “meddling in the greed that denies children health care, or a decent home, or a safe school? Who wants him challenging our easy resort to violence as the only way to personal and global security? Who wants him asking us awkward questions about why we treat the creation as little more than a convenience store filled with raw materials to satisfy our endless desire? Who wants him holding up a mirror to the deceits and betrayals of our personal lives? Better to keep him bolted [to] that manger.” (2)

Yes, indeed. We hate to see the Infant Jesus grow up so fast. He’s such a pretty little baby. We want to savor the Kodak moment forever. But it’s not just because he’s so sweet and cuddly that we hate to see him outgrow his crib. It’s also because deep sown we know that when the infant becomes a boy, and the boy becomes a man, we will be asked to grow up too.

*******

*“Turn Around,” by Harry Belafonte, Alan Greene, and Malvina Reynolds